A story of connection and friendship, formed in Vicenza, a small Italian town

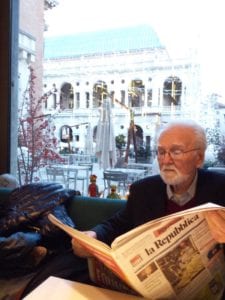

Our very own Gilli tells us how she upped her life from London and moved to Italy to teach, staying at 86 year old Danilo's house. Despite their age difference and an initial language barrier, they formed a profound friendship.

“We are far more United Than The Things that Divide Us” Jo Cox

I’d always wanted to live in Italy, well always since my first holiday in Tuscany in the late 90s. I’d done a year of beginners’ Italian and knew the vocabulary to book a table in a restaurant and pay the bill, so in September 2012 I figured I was ready to move my entire life, which consisted of a far too heavy to lift rucksack stuffed with teaching books and an oversized suitcase of winter clothes from London to a small town in a north eastern corner of Italy in the region of the Veneto. A friend of a friend, of a friend in Italy had found me a teaching job and the original friend had arranged for me to live temporarily with his 86 years old Father, Danilo who I’d never met. All

I’d always wanted to live in Italy, well always since my first holiday in Tuscany in the late 90s. I’d done a year of beginners’ Italian and knew the vocabulary to book a table in a restaurant and pay the bill, so in September 2012 I figured I was ready to move my entire life, which consisted of a far too heavy to lift rucksack stuffed with teaching books and an oversized suitcase of winter clothes from London to a small town in a north eastern corner of Italy in the region of the Veneto. A friend of a friend, of a friend in Italy had found me a teaching job and the original friend had arranged for me to live temporarily with his 86 years old Father, Danilo who I’d never met. All I knew was that Danilo’s wife had died 5 years earlier, he was in good health but, according to his son, “suffered from loneliness”. What no one mentioned before my arrival was that Danilo doesn’t speak a word of English and is more comfortable with the Veneto dialect than with Italian. After Giovanni dropped me and my luggage off at his Dad’s flat in Vicenza that first evening and the two of us went out to eat pizza with an English/Italian dictionary and paper and pen to draw our communication if things got desperate I thought I’d probably made a terrible mistake.

I knew was that Danilo’s wife had died 5 years earlier, he was in good health but, according to his son, “suffered from loneliness”. What no one mentioned before my arrival was that Danilo doesn’t speak a word of English and is more comfortable with the Veneto dialect than with Italian. After Giovanni dropped me and my luggage off at his Dad’s flat in Vicenza that first evening and the two of us went out to eat pizza with an English/Italian dictionary and paper and pen to draw our communication if things got desperate I thought I’d probably made a terrible mistake.

An English woman in her mid 50s and a very traditional Italian man in his mid 80s with limited means of communication are unlikely to have much to say to each other, you would think, but it’s remarkable how motivating loneliness can be. The only stipulation from Danilo when I moved in was that we would eat our meals together whenever possible and so began a ritual of long evenings sitting at the table after a meal while we talked. It was, in fact, Danilo who talked. My presence at the table and sharing food opened a flood gate of memories and stories from his past. My Italian wasn’t up to the job of understanding more than a tenth of the words he used but I knew enough about nonverbal communication from teaching English to watch his body language and gestures and to pay attention to the tone of voice and facial expressions. He wanted to talk, he needed to talk. I nodded a lot and smiled and said “Si”. I started to recognise the same names cropping up in stories and began to piece together the family: Mother Father, grandmother, nine children and some cousins, all living together in a large farm house with a small plot of land, a pig, cows and chickens, growing up in Mussolini’s Italy, being on the “wrong side” in the Second World War, being a partisan, seeing friends killed, trying to finish his education, finding his first job as an engineer and the long career that followed until retirement.

After the first few months the same stories started to come round again, by this time I was studying Italian several hours a week at school with other non- Italian speakers, I had homework to do which Danilo delighted in helping me with and, in particular, putting me right when I got it wrong. Hearing those stories a second time, I picked out new words and understood more. I started to grasp what had really happened between his friend Oscar and his Father, how Danilo had kept warm in the long wait between high school finishing and his train home by slipping into the University of Padua’s medical school viewing gallery and watching various surgical procedures and how he’d acquired a horse from a German officer.

He loved having a listener, the words came spilling out, Italian and dialect mixed together and as my Italian improved, we spent more time socially in each other’s company: Farmer’s market on a Saturday with a stop for coffee, Sunday morning walk with coffee in the main square, drives out into the countryside, walks in the park and invitations to family occasions. Stories came around for a third time in the second year and now I understood almost everything and what was better still I could share my own stories; stuff that I’d never told anyone. We talked about everything under the sun, about politics, religion, love, marriage, our children.

He loved having a listener, the words came spilling out, Italian and dialect mixed together and as my Italian improved, we spent more time socially in each other’s company: Farmer’s market on a Saturday with a stop for coffee, Sunday morning walk with coffee in the main square, drives out into the countryside, walks in the park and invitations to family occasions. Stories came around for a third time in the second year and now I understood almost everything and what was better still I could share my own stories; stuff that I’d never told anyone. We talked about everything under the sun, about politics, religion, love, marriage, our children.

I was supposed to stay with Danilo for a few months until I found a place of my own; I stayed five and a half years. I found “family”, I found a new language, I found an amazing friend and we both found the deep human connection that we needed and wanted.